BY ARYN HENNING NICHOLS

Originally published in the Fall 2019 Inspire(d)

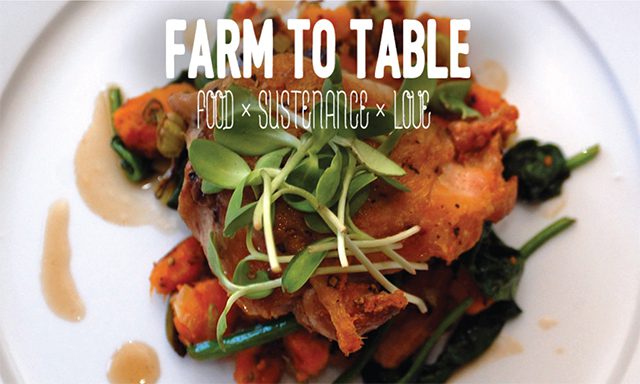

Much of Luke Zahm’s mission in life has been about creating identity.

Whether it’s as a chef, or at his popular farm-to-table restaurant, Driftless Café, or beyond that, cultivating identity for the Midwest.

“I found my identity and connection through food,” he says. “Being from La Farge, Wisconsin, I didn’t have much of a sense of place when I was younger. My mom worked at Organic Valley for 25 years, and when OV kids went off to college, we were given stacks of coupons for free products, which was amazing.”

“Sometimes I would trade them for beer,” he continues with a laugh. “Free milk, eggs, cheese, butter, orange juice – all that stuff was gold when you were in college. But often we’d use them to buy our own food. So I walked into a Whole Foods for the first time in Chicago, picked up a piece of Organic Valley cheddar, and saw La Farge, Wisconsin, written on the back, in a way that had relevance and meaning. And it struck me: ‘These are my people, this is where I’m from!’ That never left me. I loved watching the Driftless Region grow in that way.”

Before that, Luke often said, “I’m from somewhere near Madison.”

His first experience in a restaurant was a high school job at the Subway in Viroqua where, as luck would have it, he would meet the woman he’d marry someday: Ruthie Yahn.

“I was a certified sandwich artist – my Mom still has the certificate – and Ruthie was a small town princess,” Luke says, clearly settling in to tell a good story. “She was the worst customer I ever had! I was going through a Goth phase – and she came in and ordered a sandwich and was all, ‘Do you even know what you’re doing? Can I just come back there and make my own sandwich?’”

Luke, now 40, laughs. Life went on for the two – Ruthie headed to college in Tempe, Arizona; Luke in Chicago. But a restaurant would bring them together again – a Wisconsin supper club – where they both worked the next summer.

“She came to work all tan, and says, ‘Oh hey, I’m Ruthie,’ flirting, and I said, ‘Ohhh, I remember you.’”

They once again went separate ways, but eventually, both transferred to U.W. Madison. They – along with many other old friends from Southwest Wisconsin – met back up and became a tight-knit crew. And Luke and Ruthie fell in love. After they graduated in 2003 – Luke’s degree is in behavioral science and law, and Ruthie’s in nursing – they got married, and stayed in Madison for several years more.

“I thought I was going to be lawyer,” Luke says. “But I was working in restaurants the whole time, and I always felt a pull back.” To food, and to the Viroqua area as well. They moved home in 2011, with their two kids, Ava and Benjamin, in tow, and Luke went to work as an executive sous chef for The Waterfront Restaurant in La Crosse.

“I started hanging out with a lot of big chefs – getting all techy with molecular gastronomy,” Luke says. “Eric Rupert (a Madison-based chef) was my mentor, so I was telling him about all these experiments. He literally grabbed me by my head and said, ‘Dude, you are from the mecca of organics. It gives where you are so much shape and meaning. Cook that food. That’s your role.’ At the time I didn’t love hearing that. But I kinda knew it was in my DNA.”

It was a pivotal moment for Luke. He went back to the basics, spending 14 months working at the Viroqua Co-op bakery and deli.

“They opened their doors to the idea of the restaurant I wanted to create. They helped me articulate what I wanted, and gave people a chance to taste my food,” he says. It was during this time he and Ruthie had another baby, Silas. So life was busy. But they decided to take the leap to create Driftless Café anyway.

“We cashed in all our chips. 401K, savings – all of it went into this idea of this restaurant,” Luke says. “I was taking our new baby to bankers meetings, saying, ‘Here’s what we have. Loan us money!’ Nobody would do it. One day, I had a conversation with a local farmer. I was explaining my vision of what I wanted the Café to be. I wanted to put a spotlight on what farmers are doing, honor the heritage of their roots, plus what they are coming to be.”

When yet another loan didn’t come through, the previous owner of the Driftless Café came to Luke and said, “I’ll sell you the place.” Then that local farmer said, “I’ll finance it.”

“Now, I know I’m not the only farm-to-table restaurant out there… but I may be the only farmer-financed,” Luke says. “It was an amazing show of community trust. They really took a risk on this idea that Ruthie and I were worth it.”

Driftless Café opened under Luke and Ruthie’s ownership in 2013, and the restaurant quickly became a leader in local, farmer-focused dishes inspired by the region. And in 2017, Luke was named a James Beard semifinalist.

“Driftless Café’s motto is to do what it does at the highest level we’re capable of,” he says. “We want to be the authority on local cuisine, a bridge for the community, and a voice into the future.”

The same thing goes for Luke’s involvement with Viroqua Chamber Main Street – he’s been board president for the past three years. “I found I have a voice in it,” he says. “And I want my children to understand that to live and work in a community you have to be involved and active.”

The board has worked to inspire and empower future and current entrepreneurs to invest, sustain, and build up the community.

“In order to market the region, we have to capture those who are working to make things happen,” he says. In fact, years ago, Luke went to the Food Network in LA to pitch an idea for a show about food and a sense of place, highlighting this corner of the Midwest.

“They said, ‘To be fair, nobody gives a sh*t about the Midwest. All revenue is generated by the coasts. Good luck with the underwriting,’” he recalls. “Back in Wisconsin, I said, ‘Nobody gives a sh*t? I just don’t buy that.”

So when Wisconsin Foodie, an Emmy Award-winning show on Wisconsin Public Television, came to Luke about hosting the show after longtime host, Kyle Cherek, planned to step down, he was – of course – interested. After co-hosting a few shows last season, Luke took the job.

The TV spotlight might take some getting used to, though.

“I was canoeing with my daughter and her friend when another boater yells, ‘Hey, congrats on Wisconsin Foodie!’ I’m kind of an introvert, so it’s strange when people I don’t know recognize me,” he says with a laugh. “I’m trying to grow into that.”

“Maybe next time I’ll keep my shirt on,” he adds.

Life is – once again, or perhaps still – busy. Luke’s on the road four days a week filming with Wisconsin Foodie, plus working events and catering gigs, and keeping up with Driftless Café itself. He recently handed the reigns of Executive Chef over to Mary Kastman, an acclaimed chef from Boston who moved to Viroqua last year.

“Mary views and cooks with a different lens than I do, and I think that’s so important,” Luke says. “I see and taste the things she’s making and I’m floored. It’s so amazing how the same ingredients can make such different outcomes. I’m excited for her to create her own identity with food here.”

And luckily, Ruthie is – and has been – on board for it all.

“To be fair, Ruthie is the brains of the operation. Beyonce’s got it right, you know, ‘who runs the world?’ She takes care of it, and makes sure it works for our family,” Luke says. “Part of me would love it to slow down, and another part of me never wants it to slow down. When Ruthie quit job as labor and delivery nurse, we said, ‘Let’s do this thing ‘til it practically kills us.’ And when we put our heads together we could move mountains.”

At the very least – or perhaps the very best – they’ll move hearts and minds.

“Rural America feels like they’re not being heard,” Luke says. “Being from La Farge, or any small town – you’re telling me this doesn’t matter, and I’m going to prove to you that it does. I want to change how the conversation is going. I want to make sure at the end of my run with Wisconsin Foodie that people won’t ever be able to say this is flyover country again.”

Aryn Henning Nichols loves Viroqua and the Driftless Café, and is super inspired by Luke and Ruthie Zahm. They are walking their talks, and it is certainly showing.