Fireflies: The Little Lights of Summer

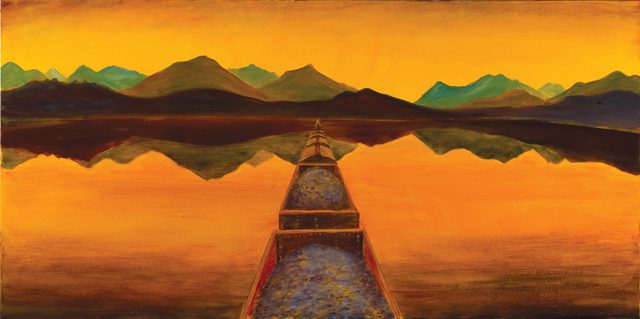

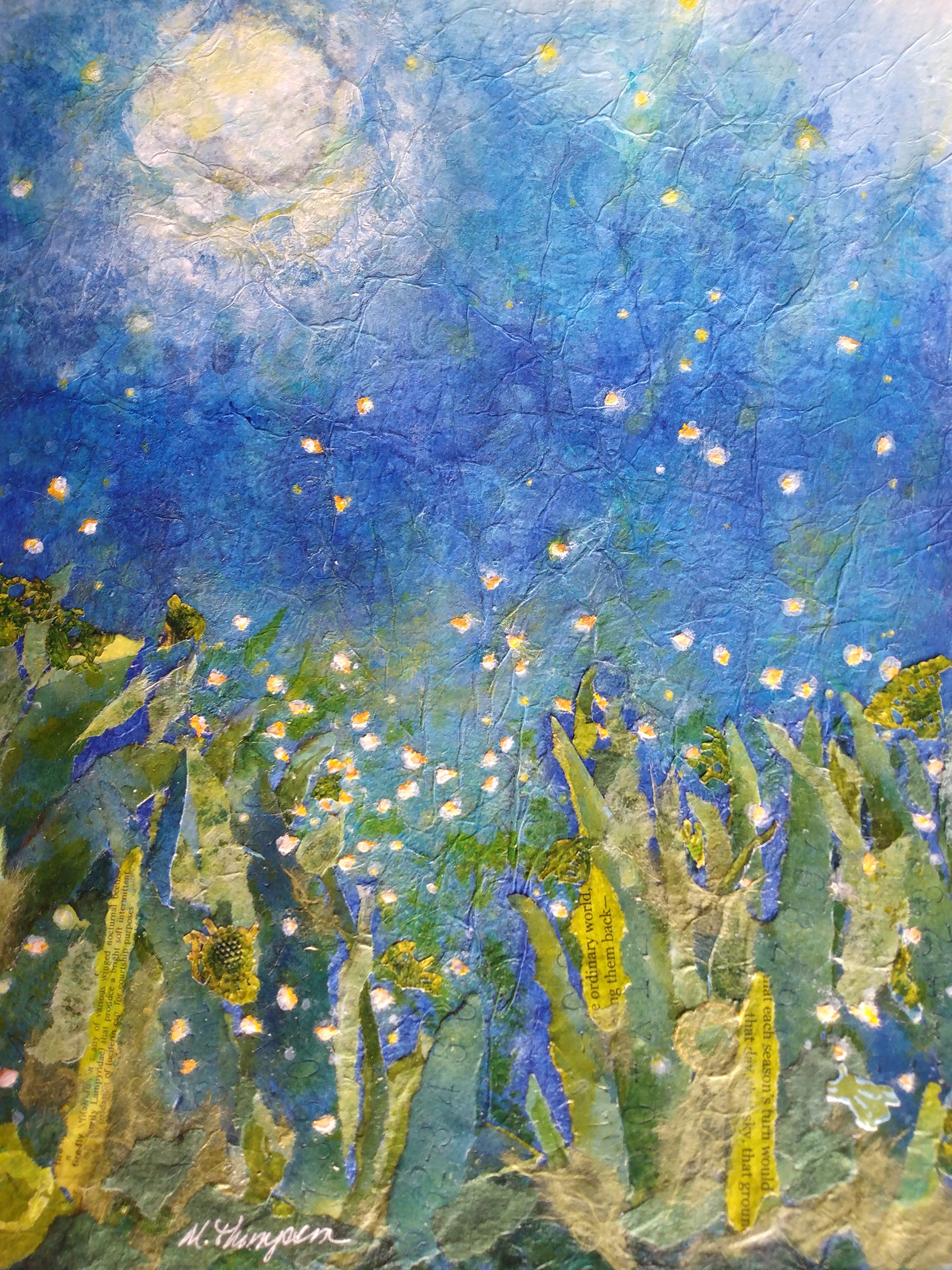

During warm summer evenings, as the sun tumbles and stars rise from their daytime slumber, a lightshow below the horizon unfolds. A single spark, then two, herald the performance. Within minutes, the flickers crescendo. As owls and bats begin nocturnal rituals, fireflies emerge by the hundreds to dance brightly, silently punctuating the darkness with tiny sparks. Bioluminescence – the production of light by living creatures – adds a tincture of magic to our backyards.

The ability to generate and emit light is widespread in nature, particularly in marine realms. Plankton, jellyfish, and even fish dwelling in the stygian darkness of deep oceans, blink, flicker, and glow.

On dry land, fireflies send bright pulses of biological morse code skyward. The purpose of bioluminescence varies by species. For some, it advertises unpalatability – “I’m bitter, don’t eat me.” For others, like deep sea fish, glowing appendages lure unsuspecting prey toward jaws filled with sharp teeth. Fireflies, on the other hand, use light as the language of love, a seductive semaphore intended to attract mates.

Fireflies are classified as beetles. Numbering more than 400,000 species (and counting!), beetles comprise almost 25 percent of all known organisms on Earth. Of that total, 2000 species are fireflies. Distributed across the planet, they burn brightly on every continent except Antarctica. Closer to home, more than 100 species inhabit North America, most found east of the Mississippi River.

Life is not always glamorous for these six-legged luminaries. They begin as tiny eggs deposited in damp mulch or leaf litter. After hatching, larvae live a subterranean existence, voraciously hunting slugs, snails, and earthworms. Depending on the species, up to two years is spent in the root zone. Larval fireflies, like their adult counterparts, are bioluminescent and often referred to as glow worms.

Adult life is short and to the point – mate and expire. In what may be the best example of an insect dating app, males fly slowly over fields and woodland edges while emitting brief flashes of light to attract females. The flash pattern varies by species. Females, ever cautious, watch while concealed in vegetation. When Mr. Bright flies by, a receptive female flashes her interest. After a brief exchange of wattage to seal the deal, mating ensues, eggs are laid, and the cycle begins anew.

Unfortunately, firefly populations are blinking out. Habitat loss, pesticides, and light pollution that interfere with mating are conspiring to drive their numbers down. Losing the little lights of summer is unthinkable.

Thankfully, we can take action to help our flickering friends. Here’s how:

• Create firefly homes by planting beautiful gardens filled with native plants.

• Leave the leaves and let logs rot. Both provide important habitat for larval fireflies. Remember – they eat pesky slugs and snails.

• Make the Driftless dark by turning off outside lights. Motion detectors can address safety concerns.

• Stop mowing all that lawn. Let some revert to habitat for fireflies and other wildlife.

• Refrain from using lawn chemicals.

Lightening bugs are an iconic part of our natural heritage. By taking a few simple steps, we can ensure their enchanting backyard lightshows burn brightly for future generations.

Mary Thompson has degrees in Fine Arts and Education. She has delighted in the creative arts since her first box of crayons. She considers a lawn chair, lemonade, and lightning bugs to be the perfect summer trifecta. She teaches art lessons to adventurous adults using a variety of media.

Craig Thompson is a professional biologist with a penchant for birds dating back to a time when gas was $0.86 cents a gallon. Some day he hopes to be as bright as his backyard fireflies.