For the Win: Women in Wrestling

In fall 2019, former Decorah high school student Meg Sessions, and her sister, Mairi, then a freshman, shocked their parents, Sara Peterson and Erik Sessions. “They came home one day and said, ‘You know, we’re going to join wrestling,’” Sara recalls. “And we said, ‘Um, OK?’ It was just left field because we have no background in wrestling. I’m an elementary teacher and Erik is an organic farmer who teaches violin,” Sara continues. “We’d never even been to a meet.”

But the opportunity was there that year, thanks to incoming Decorah High School boys wrestling coach, Lee Fullhart, a Decorah native and Iowa Wrestling Hall of Fame inductee. While at the University of Iowa, he was a three-time All-American and won a national collegiate championship, then went on to a U.S. National title and was runner-up in Olympic and world team trials.

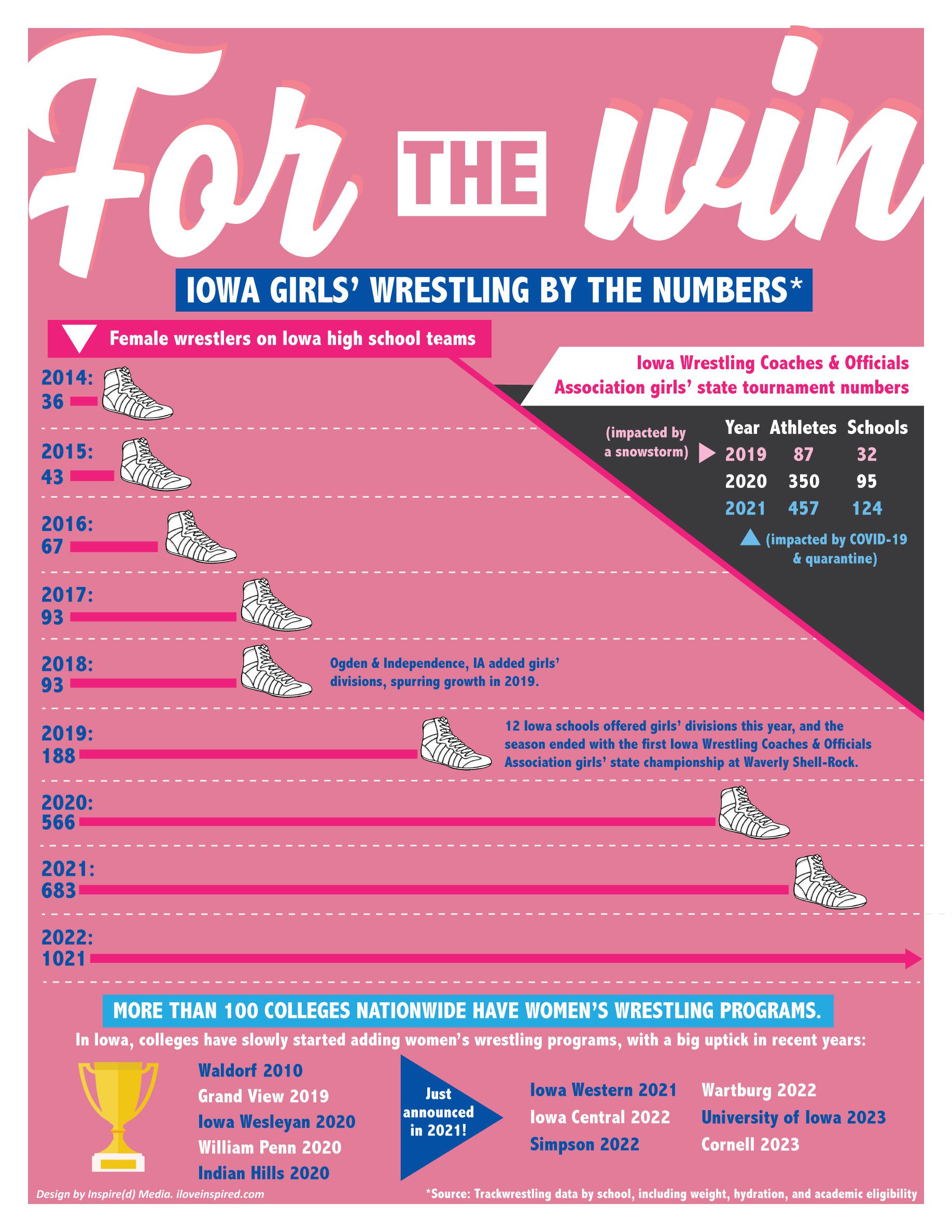

Fullhart saw an opportunity to be on the front edge of parity, and started inviting female members of the student body to follow the program. When more girls see girls wrestling, he reasoned, more girls join the sport, learning skills and self-confidence with every move. It’s working. In Decorah and across the state, girls’ teams are doubling or better in numbers with each passing year. The January 2021 state tournament fielded 457 young women from 124 schools (even in the shadow of COVID-19), up from 87 wrestlers from 32 schools in January 2019.

“We went to a couple boys’ meets the year before, and it looked like fun and good conditioning,” Meg explains. Both she and Mairi were looking to bridge the time between cross-country in the fall and running track in the spring. “They told us that if we could get six girls out for the team, then we could start one, so we started talking to people.”

Joining them in recruiting was Naomi Simon, now a Decorah High junior, who picked up wrestling as a middle-schooler on the heels of gymnastics, martial arts, and aerial training. “I think the feeling about starting a girls team was just, ‘Why not?’ If you like individual contact sports, this is the sport for you.”

Naomi’s dad, Matt, coaches her in exhibition events and USA Wrestling club championships and is also a Decorah assistant coach. “Colleges – including the University of Iowa – are building women’s programs, so this isn’t just a one-off interest,” says Matt, a former wrestler and longtime rugby player. “It’s about time girls had this opportunity, actually.”

Starting a high school athletic program – of any kind – depends partly on having athletes to fill out a team and partly on the administration to fund it, a chicken-and-egg scenario. Iowa is relatively unique in having separate athletic unions for boys’ and girls’ sports, and at the time that wrestling started to rumble, the girls’ administration didn’t have guidelines by which to sanction it in schools. This meant that districts like Decorah had no state-directed budget to pay for gym time, coaching staff, busing, or even uniforms – unless they self-funded it.

“And that’s exactly what we did,” says Decorah High math teacher Paige Hageman, now in her fourth year as Decorah’s girls’ program coach. “Our entire boys’ wrestling staff basically doubled their mat time, holding separate practices for the girls.” The private practice was necessary both to teach technique to many literal newcomers and to build team confidence, wrestling similarly skilled peers, Paige says. Some students, like Naomi, grew up with parents, siblings, or cousins in wrestling or had even been boys’ team managers. Others, like Meg and Mairi, had the will and athleticism to learn but no frame of reference.

“It’s not an understatement to say we didn’t know anything,” Mairi explains, “as in, ‘What’s a take-down?’ and ‘How many points for…what?!’ Our coaches would demonstrate something perfectly, and then I would try it, and it would be a mess,” she says with a grin. “And then, there’s putting it all together in a meet, where you have to remember all the rules and anticipate the technique.”

Meg nods. “I think our first few meets, I basically did what they told me to do, without even understanding the strategy.” Their persistence paid off: Mairi is credited with the first win in the history of Decorah’s girls’ team, and both girls went on to win their weight classes in the conference meet.

“Starting without experience isn’t always a bad thing, though,” Paige explains. “There are no bad habits to break. All you can do is learn, and get better. Our very first year, we practiced separately from the boys, which put a lot more time on the coaches, but the girls needed that space. The whole coaching staff was running practices before and after school. Our second year, we did more of a hybrid schedule, with practice with the boys a couple times/week, and some just the girls. Wrestling the boys, who had been wrestling for years, brought the girls up to speed a lot.” The girls’ team also extended their season to make up for lost time, practicing beyond their state tournament, right up until they had to get outside to run track in March.

Technique isn’t the only learning curve, Paige continues. “This is going to sound weird, but one of the biggest things I have to coach, more than any actual move, is teaching girls to use their bodies to make others feel uncomfortable. Girls are often not used to being in control of their bodies or being intimidating. It’s empowering for girls to understand that, ‘No, I’m in control, and I’m going to make my opponent do what I want them to do.’

“Along with control is teaching girls good body awareness and to fight. I ask them, ‘What if you get caught on your back?’ I mean, there’s not a lot of technicality: you just have to fight to get off your back. At first the girls were like, ‘What do you mean I have to fight? Most of them just froze, and you could almost see them thinking, ‘I know if I just wait like this, it will be over.’ I say, ‘No! Hey! You are in control! You may cause pain, and that’s a good thing, because it means you’re in control.’”

Often, parents of female wrestlers must climb that same learning curve, Sara Peterson explains. “I realized that at any given time during the season, one or both girls would have bruises on their face. I mean, I’m a teacher, where we talk all the time about being kind and not hurting each other, and this is…I’m not sure what to call it…controlled pain? I had to work up to being a parent who can keep watching [a match] to the end.”

“But then I just think it’s so brave and amazing,” Sara continues. “Here it’s one-on-one, and all eyes are on you, and you’re out there in a skintight singlet, and everyone knows your weight. And they love it. They work so hard, Mairi says, they know each other by their sweat.”

Girls’ wrestling has always had its detractors, adds Naomi’s mom, Melissa Simon, especially around issues of body image, weight, and the occasion when young women are pitted against boys in duals or meets. This naturally happens when an opposing school doesn’t have a women’s team and girls fill weight-class slots on the boys’ team.

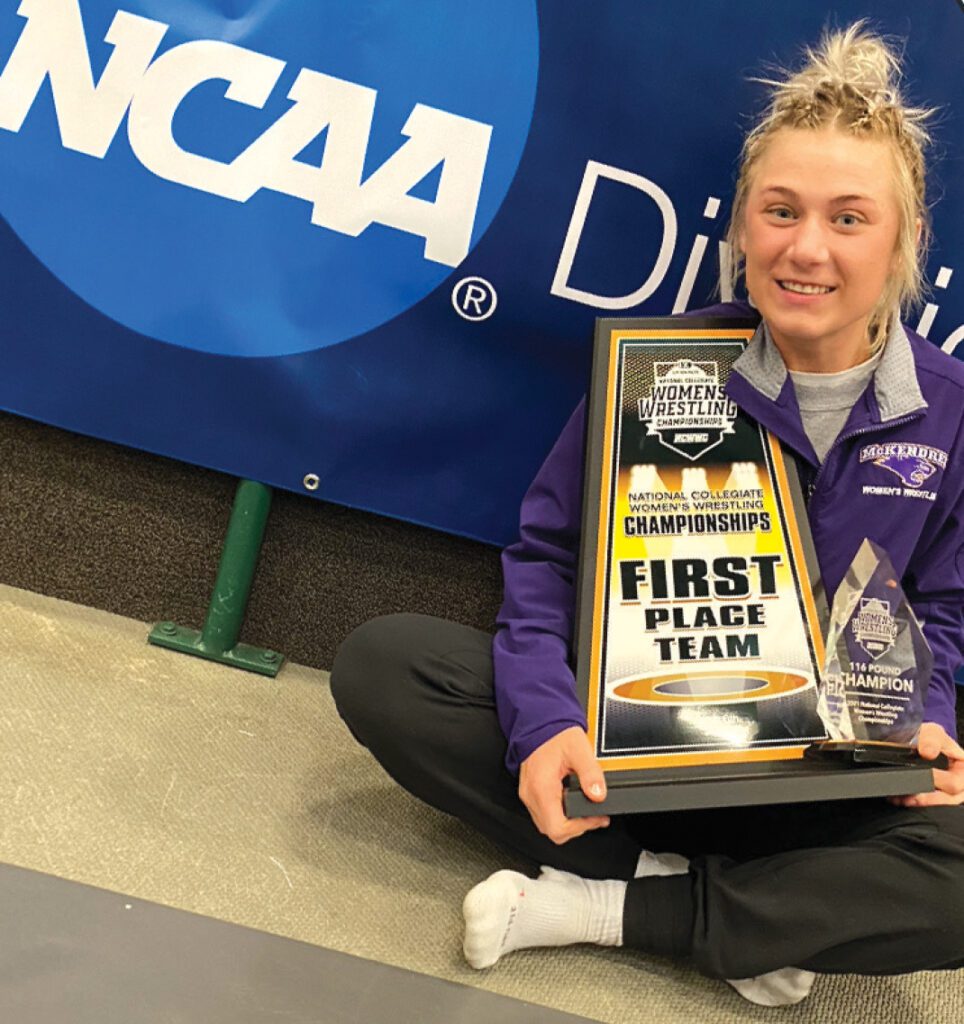

This was almost always the case for 2018 South Winneshiek graduate Felicity Taylor. When she joined the wrestling team in 2013, there were very few girls competing. After joining the sport a bit late – she started in eighth grade – she ended up rocketing that same year to a state ranking at 106 pounds (against boys), and went on to win three straight conference titles and two state championships in high school. She became the first female in Iowa history to record more than 100 wins. In the off-season, she began competing in elite freestyle club wrestling tournaments, earning All-American status and finishing second in national individual competition, while helping her team to a first-place finish in national duals and a third-place finish in national team competition.

Up until 2022, Felicity was a math education major at McKendree University, in Lebanon, Illinois, where she yet again made history as the first Iowan ever to win a national women’s collegiate championship, also helping her team to a win. Her success qualified her for both the Olympic trials and international U23 World Team trials, where she turned heads as one of the younger competitors. “My goal is to compete better,” she says of match-ups against elite wrestlers, many of whom she has wrestled before. “I go into it wanting to get back some close matches I’ve lost in the past,” she explains. Just having the prime-time experience will steel her nerves in future trials, she reasons. Felicity transferred from McKendree to the University of Iowa for the 2022-23 school year, finishing out her collegiate wrestling career back in her home state of Iowa .

“I did not think I would be an athlete in college, let alone win a national title,” Felicity says, as though she’s still surprised. But those who know her determination might roll their eyes. Originally a gymnast and a runner, she tried out in eighth grade to be a wrestling cheerleader, having tagged along to follow her older brother’s career. “I didn’t make the squad, and that shock is what did it,” she says. “I became focused on making the team as a wrestler instead, especially when I heard rumors that I wouldn’t even make it through a practice. I thought, ‘I do backflips on a 4-inch beam. And you don’t think I have what it takes?’”

Now years in the making, Felicity credits her success to her family, coaches, and small-town Driftless community. “If I had been anywhere else – any bigger school – I might not have had the chance I got,” she says. “They saw immediately that I was in it for the right reasons – to challenge myself and to improve – and they believed in me. It’s been awesome to give some recognition back by continuing to compete.”

A big part of Felicity’s legacy is her influence on younger wrestlers coming to the sport now, Naomi says. “When I was in sixth grade, I saw Felicity wrestle, and she was just…” (Naomi sits back, grasping at the right accolade) “…amazing. I thought, ‘I’m going to do that.’”

Seeing young women tear up the mat helps their parents shrug off skepticism, too, Melissa says of watching Naomi, who was state champion at 145 pounds in 2021 and 170 pounds in 2022, and who competes widely year-round. “I admit, I am NOT the quiet, calm mother in the stands,” Melissa says. “But often, it’s not the wrestlers themselves who take issue with ‘wrestling a girl’ or whether it’s ‘ladylike’ to be an aggressive athlete – it’s the adults. ‘Fragile masculinity’ is a thing. But kids are self-absorbed in the way only kids can be – they only know what’s right in front of them, and with every passing year, they forget about the time before girls wrestled, too. They’re just wrestlers, all of them.”

Decorah, for its part, prioritizes having one team, not two separated by gender. “In our first year, Fullhart took the girls’ team to a dual at a school with a notoriously tough boys’ team but no girls’ team, so we went just to warm up with the boys and support the team,” Mairi Sessions explains. “At the end, some of our opponents refused to shake our hands, as though we shouldn’t be there. But I think that was the point. We were there, and we can’t be ignored. We’re a team that is actually close. These are very cool people to be around.”

When it comes to wrestling and weight, coaches Matt and Paige explain that emphasis is on nutrition and maximizing each athlete’s potential. “Unlike other sports – especially women’s sports – where the norm is to all look the same and where there’s some societal expectation of conformity, we actually need all shapes and sizes for the roster, from 106 pounds to 285,” Paige explains. And as girls get strong, Matt adds, the concept of ‘cutting weight’ often goes out the window. “More often, it’s difficult for girls just to maintain (not lose pounds). We talk a lot about making sure they’re drinking enough water and getting enough sleep. Once you figure out nutrition and how your weight works, you’re on your way to peak performance, and those are skills that will serve you for the rest of your life.”

On the wider stage, Decorah is among several Northeast Iowa communities that have formidable girls teams, including Osage, MFL-Marmac, and Waverly-Shell Rock, which hosted the first-ever girls’ state tournament in January 2019 (sponsored by the boys’ athletic union). And at the administrative level, support is building to sanction girls’ wrestling state-wide, spear-headed by club wrestling organizations and champions within each school district.

Charlotte Bailey, women’s director at Iowa USA Wrestling and founder and coach at Female Elite Wrestling (FEW), a nonprofit and sanctioned USA Wrestling club in Iowa City, is arguably among Iowa’s strongest supporters of girls’ wrestling. She and her coach-husband George founded FEW to support girls’ development as wrestlers, advocate for equity in the sport, and assist athletes with access to national and international competition.

“My daughter, Jasmine, wrestled,” the former gymnastics coach explains, “and yes, she was out for her high school team with a great coach, but her real opportunity in the sport was in freestyle wrestling – Olympic style – in the off-season, to prepare for college and a shot at Team USA. That led me to be more involved.’

“At the time (2011-14), there was a huge gap in opportunities for the female wrestler,” Charlotte says. “There were places where Jasmine was not welcome, and people went out of their way to dodge competing with her. I wanted to help change the culture and create a space where girls and young women had more opportunity, and in particular, opportunity to compete against other girls. FEW was founded to connect people across the state and provide practices for girls, led by women, with the goal of competing as a team. By creating all-girls wrestling divisions and stand-alone tournaments, FEW made it so girls new to wrestling or trying it out, didn’t have to go to a big national tournament nine hours away by car and spend three days in a hotel in order to wrestle their first match against a girl. We bring the opportunity to wrestle girls here.”

Charlotte’s decade-plus of advocacy has since earned her induction to the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and propelled individual FEW wrestlers to national and international recognition. She’s also at the nexus of efforts to shepherd girls’ wrestling in the schools. The Iowa Girls Athletic Union required a total of 50 high schools (or 15 percent of schools in the state) to submit a letter of commitment to the Iowa Wrestling Coaches & Officials Association (IWCOA) declaring support for their own high school program. Now that the quota has been met (as of October 30, 2021), an advisory group will work through regulatory details and scheduling to make sure what they’re proposing works for the schools that have already committed. Then the union could approve the sanctioning of girls’ wrestling and create a timeline for it to become official. (Update: The Iowa Girls High School Athletic Union Board of Directors voted unanimously to sanction girls wrestling as the organization’s 11th sport. The 2022-23 school year was the first IGHSAU-sanctioned girls’ wrestling season.)

“Where wrestling really grows and thrives across the country, is inside schools,” Charlotte concludes, “where the high school coaching staff can be there with those girls, in their corner. These athletes want to rep their schools, wear their school colors, and represent in championship competition. Recognition as a sanctioned sport makes all the difference in the world.”

For the athletes, stepping onto the mat as an individual, backed by an enthusiastic team, is profoundly validating, Naomi Simon explains. “We put in the time, learning to control emotions and just wrestle to the best of our ability. I gain a lot of self-confidence from it,” she says, “and my teammates do, too.”

Kristine Kopperud

Kristine Kopperud is a writer/editor and end-of-life doula. When not cleaning her floors to avoid looming deadlines, she’s usually at the riding barn, watching her daughter’s horse lessons. Read more at kristinekopperud.contently.com.