Saving Our Soil

It’s not uncommon to see Dr. Jodi Enos-Berlage, a biology professor and researcher at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, lugging a decent-sized clump of dirt around the lab.

But no, it’s not dirt – that’s too small a word. This is Soil. A teaspoon, if it’s healthy, holds a huge community – billions – of bacteria, protozoans, fungi, nematodes, insects, and more.

“The life below makes the life above possible,” Jodi says. “Soil is the literal foundation of life. Over half of life on earth lives in the soil.”

Not only that, soil produces 95 percent of food and is one of the most cost-effective ways to sequester carbon. It absorbs, stores, and filters our water. Its microbes recycle nutrients to enable new life for the world above, and those microbes are also the source of the vast majority of antibiotics.

From Watersheds to Soil Health

In 2009, as Luther’s microbiologist, Jodi was asked by Iowa State Extension to lead a water monitoring project for Northeast Iowa’s Dry Run Creek Watershed, which had high levels of bacteria. While environmental monitoring wasn’t Jodi’s primary area of expertise, she was drawn to the project. She grew up on a beef farm in small-town Illinois, giving her a foundational understanding of the connections between water quality and agricultural activity, and she and her husband own a farm in the Dry Run Creek Watershed. She also knew the project would offer great student research opportunities and expand her own repertoire in a way that connects to the community.

So, between 2010 and 2015, Jodi and a student team monitored 10-14 different sites under rain and non-rain conditions. Results were reported to the Dry Run Creek Watershed Improvement Association and published in the journal, Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, and the 20,000-acre watershed became one of the most monitored streams in Iowa.

“Saying yes to this project basically changed my whole career trajectory…and laid the groundwork for the future projects on soil,” she says.

After 15 years of study, it was clear to Jodi that poor water quality and flooding are symptoms of degraded soil. Healthy soil acts like a sponge; degraded soil sheds water, leading to flooding and poor water quality. And while the Midwest holds some of the richest soil in the world, research conducted at UMass Amherst by Iowa native and geoscientist Dr. Isaac Larsen indicates that we’re losing it 10 to 1000 times faster than it’s formed. A big part of this is because most Iowa fields are empty during the non-growing season, with no plants or living roots to protect the soil and feed its microbes. Without those roots, soil microbes are starving. Plus, any kind of tillage acts like an underground tornado, further destroying microbial communities and making soil more vulnerable to erosion.

“One-third of the corn belt has already lost its topsoil completely. Some soils are nearly dead,” Jodi says. “But this problem is fixable. And we know how.”

The solution is to mimic nature as closely as we can. By minimizing soil disturbance (no-till), keeping living roots in the ground year-round (cover crops/perennials), keeping soil covered (plants/residue), increasing diversity (rotations/cover crops), and integrating livestock (if possible) – farmers and landowners can turn this around, literally regenerating topsoil.

But the first step is getting all hands on deck. It was during her watershed work that Jodi realized outreach materials weren’t reaching women landowners and farmers, including herself. As the only woman at the table, she asked why. The reason? They didn’t know their names. “Women weren’t listed in the plat map books,” Jodi says. “I called the plat map CEO and he said they just list whoever is written first on the deed, which is hardly ever the woman. So I knocked on every door in the watershed to learn their names.”

Jodi then dug into the research, learning that women own nearly half the land in Iowa – 47 percent – and the majority of the rented farmland. “Studies show women tend to care deeply about conservation, collaboration, and community,” Jodi says, “Yet we feel less knowledgeable about regenerative practices, resources, and networks.”

This felt like a significant and powerful untapped resource and one Jodi could help foster.

“As a farmer, educator, scientist, artist, and mother, I live at an ‘intersection’ of many different communities,” Jodi says. “This means I can help bridge gaps. We will not solve the soil health crisis in Iowa without all the different communities at the table. We need women there – and it is our responsibility to do our part.”

In 2018, Jodi scrapped the entire microbiology laboratory experience she’d developed over her first 18 years at Luther. She converted her lab into a semester-long research project focused on crowd-sourcing antibiotic discovery from Northeast Iowa soil microbes, as part of the Tiny Earth consortium. Based out of UW-Madison, Tiny Earth aims to engage scientific research that addresses diminishing antibiotics, the rapid decline in soil health, and the need for more scientists in the workforce. Jodi knew the Tiny Earth founder, Jo Handelsman, from Jodi’s Ph.D work at UW, and was greatly inspired by both the Tiny Earth mission and Jo’s book about the catastrophic loss of topsoil, A World Without Soil.

Empowering the Unseen

In 2023, after five years of soil work in the lab, Jodi felt called to create The Power of the Unseen, a TEDx talk focusing on unseen soil microbes and landowners and their collective power to regenerate soil. It lit a fire.

“When soil life gets better, lots of other good things happen automatically. Water quality goes up, flooding goes down, carbon gets pulled from the air and goes into the ground. The soil fertility increases, and we can grow more food using less inputs, making this a win-win-win for farmers, eaters, and water drinkers…and frankly, our collective future on the planet,” Jodi says. “As someone who’s driven by positive impact, how could I not pursue this?”

She wanted to take this research and apply it in the larger community. The final piece of the puzzle was funding.

“I wrote and submitted a small soil-focused grant within 48 hrs after my TedX talk,” she says. After asking local soil health professionals for feedback, she found out about a much larger grant opportunity, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) subaward to the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

“We assembled a dream team of sorts,” Jodi says, citing partners from Luther College, the Winneshiek County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD), and Northeast Iowa Resource Conservation & Development (RC&D). Core project leads included Sophia Campbell, who then was with Winneshiek County SWCD and a key connector to landowners, and Ross Evelsizer from Northeast Iowa RC&D, who was a valuable partner for both his grant-writing know-how and his talents for communicating with broad audiences.

The land itself was an unwitting partner as well. The Driftless Region’s highly erodible ground and karst topography makes it vulnerable, with data showing that soil and water deterioration is occurring here at a faster-than-average rate. In fact, many area farmers are already working on solutions.

“We’re not starting this regenerative agriculture revolution. It’s already happening in the Driftless Region. We know this because we’ve been on and learned from their farms,” Jodi says. “We’re trying to do our part to catalyze and accelerate the work, helping the movement spread faster. I firmly believe we can be a model for the state. As I wrote in the grant, ‘Lead we must.’”

The team wrote two interlinked proposals in less than six weeks, and were quickly awarded a four-year grant, which they collectively titled Regenerating Soil and Community, with funds totaling $471,450 from the Iowa DNR/EPA. In addition to Jodi, Sophia, and Ross, the team includes Luther faculty Gwen Strand (Biology), Dr. Laura Peterson (Environmental Studies), Dr. Rachel Brummel (Environmental Studies), and Jane Hawley (Dance).

The mission of the Regenerating Soil and Community (RSC) project is to grow knowledge, networks, and strengths in order to address barriers landowners and farmers experience as they work toward improving soil health on their land.

Eligible participants – women, beginning farmers, those with limited resources, veterans, and socially disadvantaged – must live within 25 miles of Decorah (an area encompassing portions of six counties and five active watershed projects), commit to one season of project involvement (12-18 total hours), provide land use history and access for soil testing, participate in confidential pre/post interview conversations, and engage in at least two project networking/learning events.

So far, with one cohort completed and a second in-progress, participants have all been women. The fact that women landowners and farmers have expressed the strongest interest makes sense to the team, given the percentage of Iowa land owned by women.

Fresh Recruits

Sophia Campbell shifted from working with the SWCD to becoming the Trout Run Siewers Spring Watershed Project Coordinator at the Iowa DNR in early 2025. Project Coordinators like Sophia are the boots on the ground professionals who work in specific watersheds.

Sophia also shares information about programs that incentivize regenerative practices like cover crops, no-till, and the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which encourages landowners to convert environmentally sensitive acreage into perennials in exchange for annual rental payments and cost-share assistance, or Timber Reserve, which offers property owners tax exemptions for eligible timber land to promote sustainable forestry practices, protect watersheds, and enhance wildlife habitats. Many landowners in the area already know Sophia through this work, so she was a key connector and recruiter for RSC’s cohort one and two.

“That gives our cohort members a local person to go to as a resource. Someone they can build a lasting relationship with who cares about their farm’s success and legacy,” Sophia says. “Project Coordinators and other conservation professionals often share this fondness or appreciation for the land, wildlife, plants, water…and we grow these memories with the farming community when we work on conservation projects together.”

Cohort Camaraderie

The five women from cohort one gather around a table, sipping coffee and nibbling muffins, chatting as though they’ve known each other for decades. The collective power at the table is downplayed, humbled by a Midwestern upbringing and a system unused to women making the decisions.

But these women are in charge of acres and acres of Iowa land – an incredibly valuable and vital commodity – and through the Regenerating Soil and Community project, they’re learning that knowledge equals strength, and they’ve got both in spades.

Mary Crawford & daughter Stacy Davi

“They said, ‘free soil testing.’ So, I’m like, sure,” Stacy Davi says with a laugh. In cohort one with her mother, Mary Crawford, Stacy, along with her mom and her brother, Chris Crawford, manage their family’s 180-acre heritage farm in Frankville.

The three formed a farm LLC after Mary’s husband – Stacy and Chris’s dad – Darrel, passed away in 2018. “I wasn’t really involved before that, so we had to scramble to make a plan,” Mary says. “But now, with what I’m learning about the ways to preserve your soil, I want to be more involved so we can have good soil to pass on to the next generation. I feel so thankful now it’s the three of us, equally sharing the decisions.”

Darrel was involved with County Soil & Conservation and was using conservation practices on their land until the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. This major economic crisis devastated agricultural communities and rural main streets throughout the Midwest and across the nation.

“I was a teacher and Darrel was farming, and when the crisis hit, we had to sell a lot of our land. We were farming close to 1,000 acres through ownership and renting,” Mary says. “Rather than declare bankruptcy and lose the original farm, we sold some land and all our machinery so we could pay off the federal land bank. But then we couldn’t even farm.”

So, Darrel and Mary both worked jobs off the farm. After selling more than half their acreage, they managed to keep the 180 acres that they would rent out from the 80s through today.

Farm rentals are the norm these days. According to the 2023 Iowa Farmland Ownership and Tenure survey, 58 percent of farmland is leased, with the majority being cash rental arrangements – a topic the women discuss with frequency, along with other hurdles and opportunities they experience as landowners.

“Being part of this cohort was really empowering,” Stacy says. “Hearing what other landowners are doing and then just sharing our stories…it’s great not feeling like you’re in this silo alone.”

Denise Buddenberg

Denise Buddenberg and her then husband bought 80 acres and a dairy barn near Waukon in 1984, right about when the Farm Crisis was peaking.

“We didn’t really have much then, so that’s how we survived it,” she says. “A lot of classmates of mine that had bought a lot of land and a lot of green machinery… they went under, and then we just lost a whole generation of farmers.”

In 1992, they bought “the Klinkenberg farm,” adding a little over 200 acres, and in 2001 they expanded the dairy to a huge freestall barn. “Because that’s what all the ag people tell you: You got to get bigger, or get out. So we got bigger,” Denise says. And then, in 2001, she had a stroke. “And then I had open heart surgery. And then two eye surgeries,” she says. “Mary helped me get through all that mess.”

“She’s a tough girl,” Mary says with a soft smile at Denise, her long-time friend.

Recovery took a while, but, like most farmers you’ll ever meet, Denise kept giving it her all. Life events continued, with a divorce in 2010, a splitting of assets, and her parents passing away in 2021. Denise inherited 240 acres, with 180 in timber reserve, some in CRP, and some rented as cropland. She’s the sole owner of upwards of 500 acres.

“Yeah, I was pretty lucky,” she says. “But on the flip side, I really worked hard for a long time to get there.”

Nancy Bolson

“I’ve got a bumper sticker I need to get on my car,” Nancy Bolson says with a short laugh. “It says, ‘Don’t treat your soil like dirt.’” Nancy and her two sisters inherited their 126-acre farm near Ossian from their parents in 2006. They have land in timber reserve, prairie, and rented cropland.

“It’s a shared responsibility with my sisters,” Nancy says, although she and her husband handle a fair amount of the day-to-day management. “I work with the renter and the prairie and kind of try to keep my finger on the pulse of the farm operation.”

There have been some regenerative practices in progress on her family’s land for years, and renters know it’s desirable for its high-quality soil. Nancy and her husband also rent out land on an additional 173-acre farm near Burr Oak. She believes farmers are looking for land of any sort, and many would be willing to try regenerative-style farming to get access to more acres. “I mean, people want land,” Nancy says. “I know there are other people out there that will do cover crops and no-till. I get cold calls of people wanting to rent our farmland. To rent it out from under our renter.”

Sheri Borcherding

Sheri Borcherding and her husband bought their 240-acre farm north of Decorah, whimsically named Camber Castle Farm, in 1964.

“And just as a point of interest, we paid like $315 an acre. At the time, land was selling for around $200 or maybe even $150 around us. So, I’m sure the people thought, ‘Boy, those people really got screwed over when they paid that much for it,’” she says. “The 120 behind me last fall sold for $14,785 an acre. So, you can see what land has done. I mean, it just blows me away when I think about it.”

Sheri and her husband farmed the land until they decided to rent in 1990.

“We did everything wrong,” she says in regard to regenerative ag practices. “We plowed, we disced, we dragged, we planted.”

The women are quick to defend each other. “Because that’s the way it was! In order to be a good farmer, that’s what you did,” everyone chimes in.

Sheri’s husband passed away in 2018, making her the property’s sole owner. She lives in the farmhouse, and her long-time renter maintains the farm – 17 acres of woods, the rest in cropland. He has done many things to help conserve the soil, Sheri says, like putting in grass waterways and practicing low tillage.

All the women agree that talking with renters about converting land over into conservation practices is complicated. Sheri thinks of her renter like family and doesn’t want to push things too far, but she also feels strongly about soil health. “We have to save something for the generation coming up,” she says.

The camaraderie amongst the women in cohort one has been a bright star in an already shining sky. “I didn’t expect quite so much fellowship among our cohort members and willingness to share knowledge and perspectives,” Sophia says. “I am genuinely brought to tears sometimes over how great this community of people has been to work with.”

The Experiment in Progress

Cohort one plowed the path for the remainder of the Regenerating Soil and Community project. Denise even hosted a party on her farm to welcome the second cohort in June of 2025. From there, the process began again.

Early summer, an RSC team – generally one Luther student, two faculty members, and one project partner – will meet with the landowner at their kitchen table to learn their farm story, challenges, and goals. Being the Midwest, baked goods are often present.

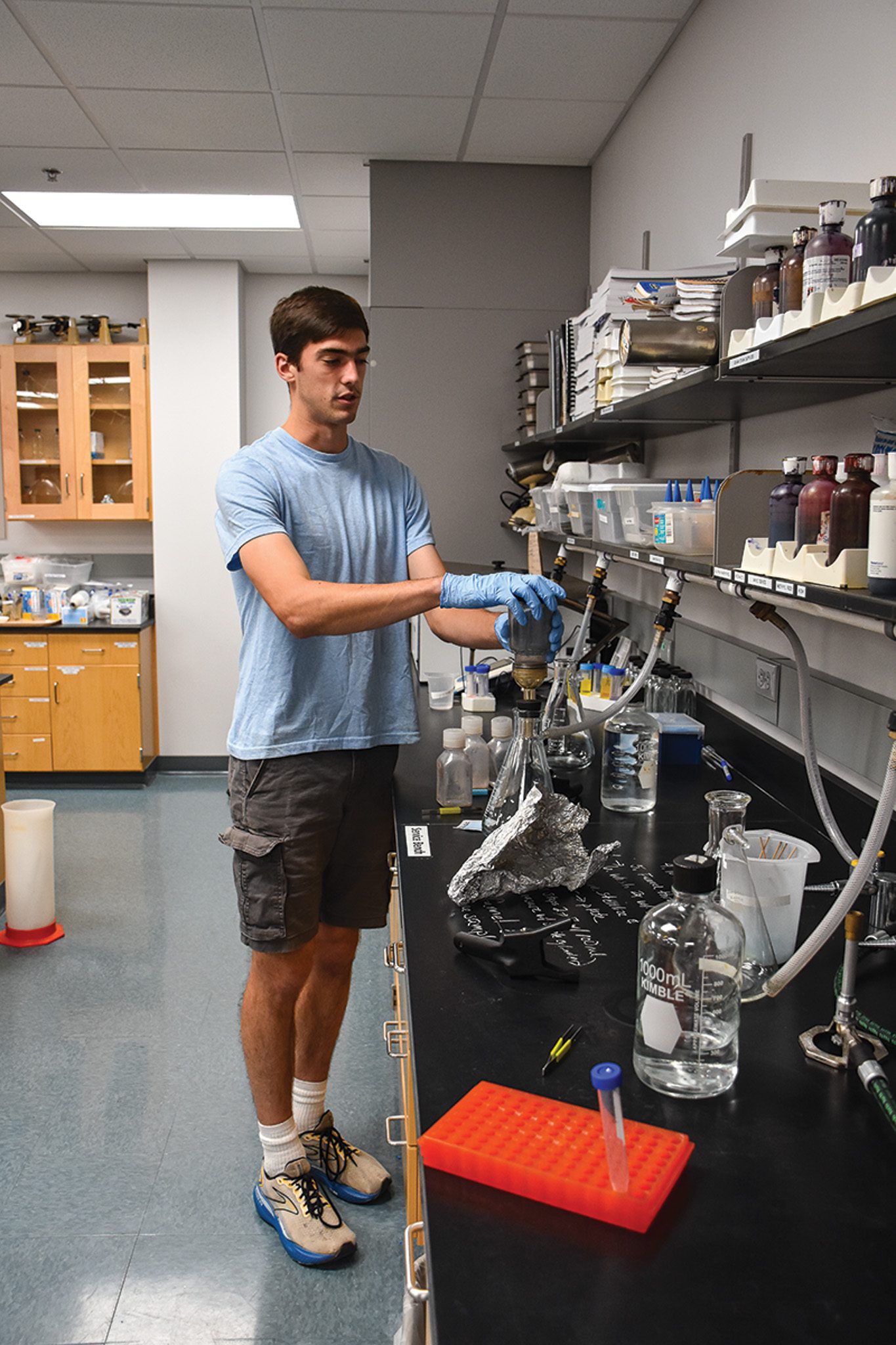

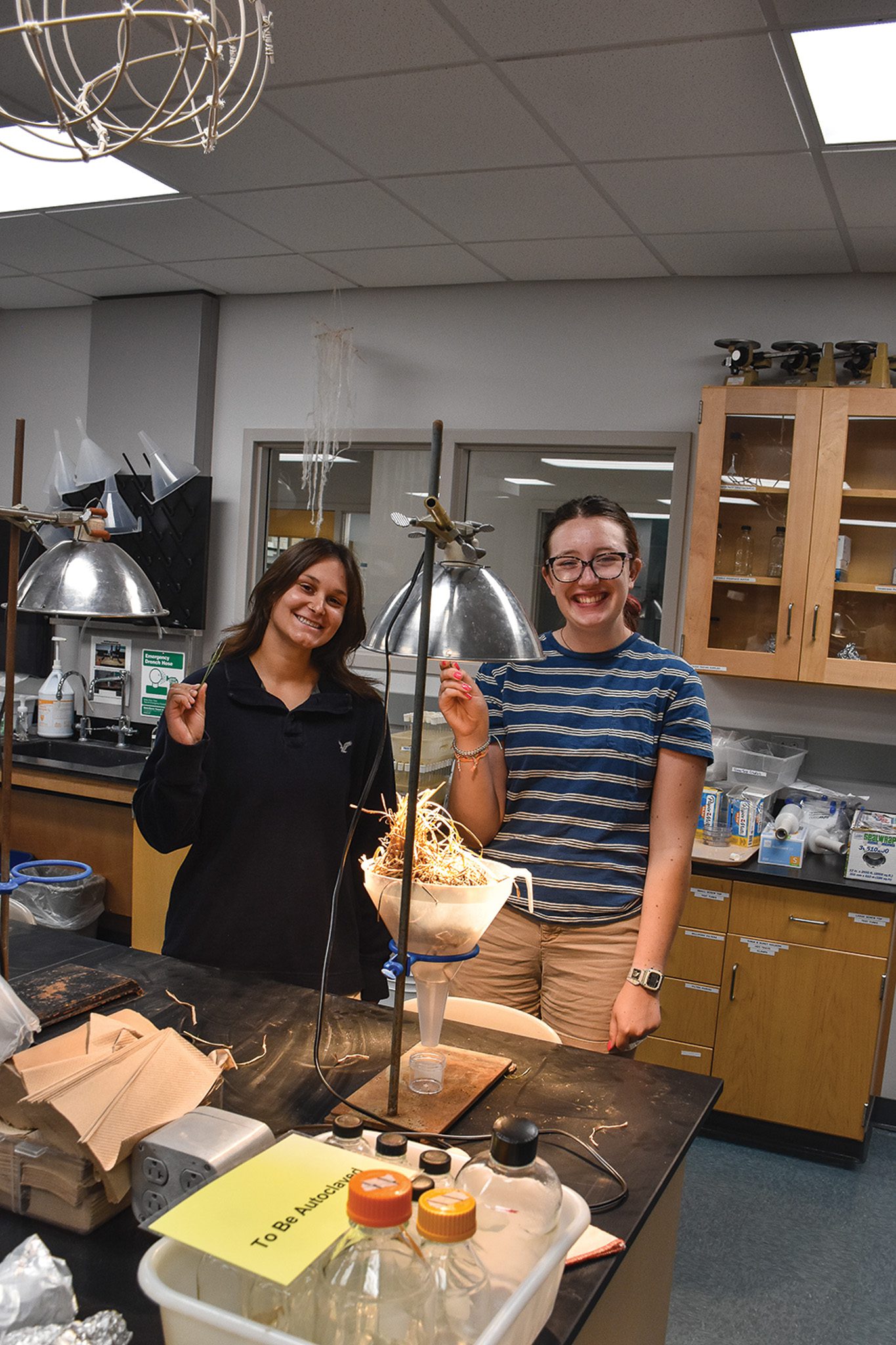

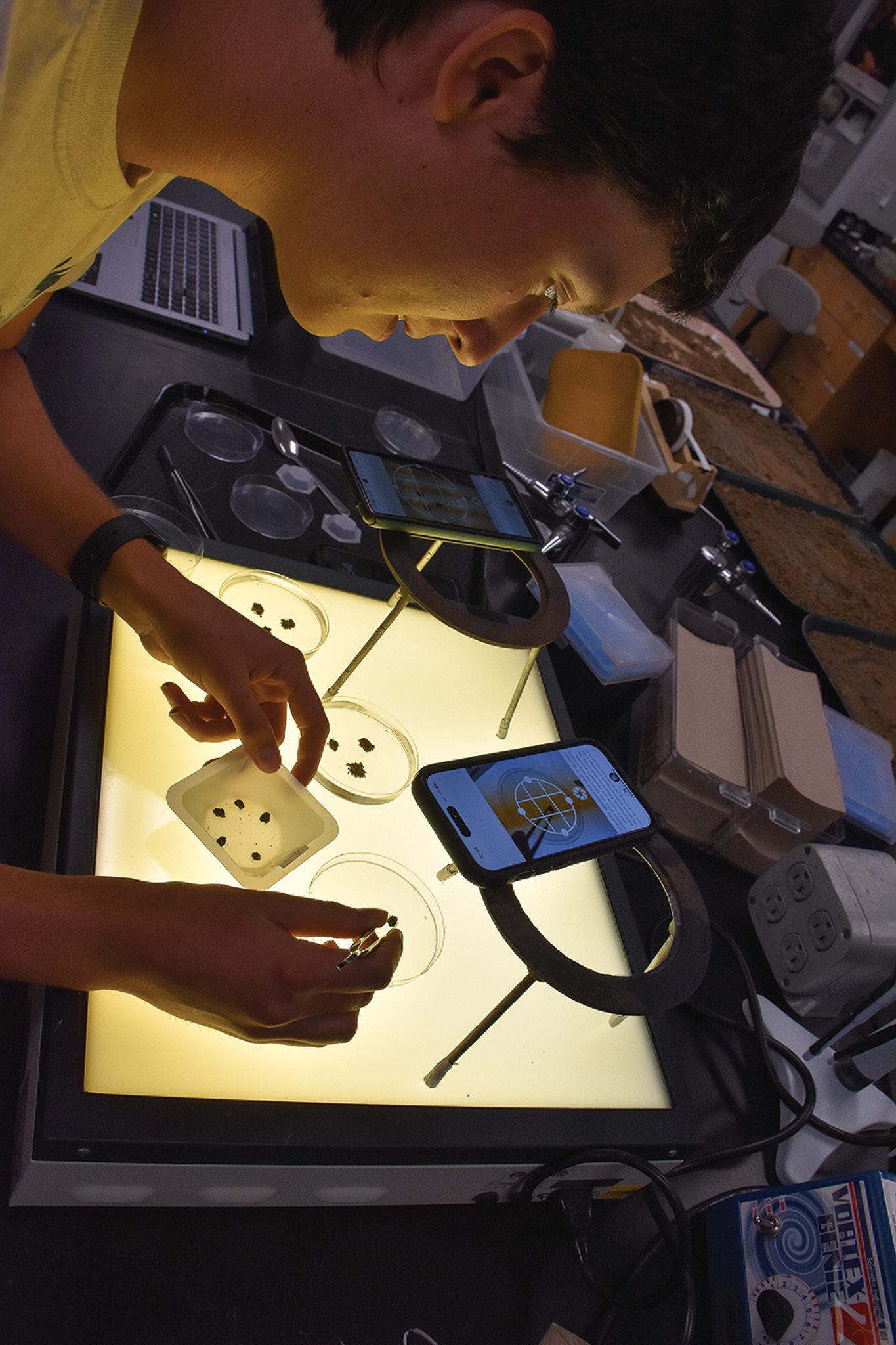

A week later, eight RSC members will spend a full day pulling 200 six-inch soil cores and taking around 20 water samples from different sites across the property. They immediately start processing samples in laboratories at Luther and also partner with Cornell University Soil Health Lab in Ithaca, New York. All results are shared confidentially with the landowner.

While soil and water testing is in progress, each cohort member takes the CliftonStrengths assessment, developed by Gallup, which identifies an individual’s top five strengths. Jodi, a certified CliftonStrengths coach, then guides each cohort member through their results, helping them understand the strengths behind their patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving.

“I thought, ‘This is a little freaky. Do I really want to know this?’” Nancy says, remembering her first reaction to the assessment. “But when we looked at the answers, I started to get it.”

“It really helps that Jodi coaches you after you get your results,” Mary says. “That you should be proud of your strengths.” Then, they learn to apply those strengths in their personal and professional lives, as landowners and beyond.

RSC students and faculty take the assessment as well, immersing themselves in the process. Each faculty member helps guide students as they learn from, form relationships with, and do research for their rural neighbors, as well as play a central role in public engagement and outreach.

“The students have been fantastic…deeply curious, hard-working, with outstanding teamwork abilities. They know this work matters and can positively impact our community to address very real needs,” Jodi says. “We’re all learning as much as the cohort members – this level of immersion experience can be life-changing for students and faculty alike.”

After soil and water testing is well underway, cohort members are welcomed for “An Evening at Luther Laboratories.” Labs are decorated with streamers amidst the beakers, equipment, and tech, and snacks and drinks kick off the fun night. Then landowners don lab coats and rotate through seven different student-led stations to experience the testing that was conducted on their soil and water samples.

And finally, at the completion of the cohort year, each landowner gets a professional, high-quality report detailing their farm visit, coordinates of all their soil and water sampling sites, farm visit photos, highlights of their strengths and interviews, and all of the field and water sample data results and analysis.

As far as the RSC team is aware, there’s not a soil/water project like this happening anywhere else. And while the entire project has been and still is an experiment, Jodi says outcomes have surpassed nearly every expectation. “This Margaret Mead quote feels like it sums up what we’re doing: ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.’”

“That’s been a big part of the success of this project,” Jodi continues. “There is no person on this team who is not highly committed.”

The first summer was like a startup, building infrastructure and delivering results in eight weeks. The second summer was like a 2.0 version, applying what they learned to improve the process.

“Every day, we’re adapting and experimenting with what works better,” Jodi says. “Without question, we have grown knowledge, networks, and strengths in cohort members and ourselves. It’s exciting and powerfully motivating. Change is possible.”

To date, all members of cohort one have had meaningful conversations with family and/or tenants about increasing regenerative agriculture practices on their farms, and many have initiated steps to further their land transition planning. One cohort member has joined Climate Land Leaders and initiated a program with the Savanna Institute for agroforestry. At least two have signed up for cover crops, and a third has discussed integrating perennial strips with her tenant, who is developing plans. And, finally, a fourth member requires no-till and cover crops in her lease and is sharing this model with others.

What does it cost NOT to do it?

“The easiest way to explain regenerative ag is to just grow more things,” Northeast Iowa RC&D’s Ross Evelsizer says. “That’s all we’re asking people to do. Grow more types of crops, grow more things throughout the growing season, for longer. Don’t disturb the ground, chemically or physically, and grow more things.”

The Regenerating Soil and Community project felt completely in line with Ross’s goals with RC&D, where he’s worked since 2013.

“The first cohort was the dream scenario. It came together better than we could have scripted it,” Ross says. “We had five women that were all at different places with their understanding of regenerative ag. We tried to elevate their understanding of land practices and conservation and their rights as landowners to the same or similar level. And then from there, they can make decisions about what they want to do next. Most that participated last year were very interested in conservation and doing more regenerative ag stuff after learning about how it all works. That’s a win for us.”

Generally, you have to commit some years to it to see a cost benefit to regenerative ag, and that can be scary, Ross says. But it’s best to think of it as a long-term investment, especially with the average value of land being almost $11,500 per acre. And then, you’ve got to think about how you’re taking care of that investment.

“We’re on the verge of the largest land transition in history since the Louisiana purchase,” he continues. “The boomers are aging out, and they are the largest singular generation of landowners in the U.S.”

According to the Iowa Farmland Ownership and Tenure survey, two-thirds of Iowa farmland is owned by people 65 years or older, and 37 percent of farmland is owned by people aged 75 or older. “Eventually, land with high quality soil will be worth much more than land that has been abused for years.” Ross asks. “What will it cost you to NOT do regenerative ag?”

But it’s not too late, even for these folks.

“We’ve always heard it takes like 100 years – or a lot more – to build an inch of topsoil. But what we’re seeing with people who have switched to full-on regenerative ag is an explosion of biology in the soil,” Ross says. “They’re bringing the soil back to life. It’s not dead anymore. Not just not dead, but really healthy… really good soil within three to five years. Just by growing more things. That’s all we’re asking. Don’t till more, grow more.”

Ross sees the Regenerating Soil and Community cohorts as another incredibly important thing to grow.

“We added five cohort members this year. Joining the others, we have ten. And they all have friends. And then they can act like mentors, helping them gain a little more confidence,” Ross says. “And then pretty soon, you’re putting these powerful women out in the landowner community… yeah, it’s gonna be an uprising.”

Aryn Henning Nichols

Inspire(d) editor Aryn Henning Nichols loves projects that involve lots of different cross sections of people coming together. And geeking out in science labs! She is inspired by the powerful female landowners and the leaders behind RSC.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE RSC PROJECT

Keep an eye out for RSC community outreach efforts, like local film showings, the Dreaming of Fields event each summer at Pulpit Rock Brewing, Impact Coffee Trivia Night, and more.

The RSC team also developed a Regenerating Soil and Community Travel Bingo game, with squares for things that can be observed while driving the Iowa countryside, like cover crops, livestock, grassed waterway, etc.

Learn more about RSC & download a bingo card at:

winneshiekswcd.org/regenerating-soil-communities-initiative

—————————————————-

Videos relating to the Regenerating Soil and Community Project

• Watch Dr. Jodi Enos-Berlage’s The Power of the Unseen TEDx talk: shorturl.at/fx5Ft

• Watch a recording of Soul of Soil: shorturl.at/EaSvE

Soul of Soil was a 2024 collaborative dance project between Jodi Enos-Berlage and Jane Hawley, Luther College professor of dance, that merged science and the arts. “It was one of the highest-impact things I’ve ever done in my 25 years at Luther,” Jodi says. This production is essentially the sequel to the highly acclaimed 2015 science/dance production, Body of Water. Soul of Soil was performed before sold out audiences each night, even bringing some members to tears.

—————————————————-

While we’re talking conservation, add this to your to-read list:

We Can Do Better: Collected Writings on Land, Conservation, and Public Policy by Paul W. Johnson and edited by Curt Meine

In the story of Iowa’s Soil and Water through the late 1900s and turn of the century, Paul W. Johnson was a hugely important figure, advocating tirelessly for conservation and public policy that supports it. Paul spent his early years in Illinois, did Peace Corps missions in Ghana, W. Africa, pursued further education in Michigan and Washington, and had several world-broadening adventures in Honduras and Costa Rica. Then, in 1974, Paul and his wife, Pat, moved their young family to a Northeast Iowa Dairy Farm.

He would go on to serve three terms in the Iowa House of Representatives, helping secure such groundbreaking bills as the Iowa REAP (Resource Enhancement and Protection) Program, the Groundwater Protection Act, and the Leopold Center for Sustainable Ag at ISU. In 1993, Paul was appointed Chief of the Soil Conservation Service (SCS, later known as the NRCS) by President Bill Clinton, and would become the head of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources under Governor Tom Vilsack in the 2000s. During all this time, Paul and Pat continued to run Oneota Slopes Tree Farm and also managed sheep and dairy herds.

In Paul’s later years, family friend Ellen MacDonald recorded hours of interviews with him that became The Life of Paul W. Johnson, in His Own Words: An Oral History.

Ice Cube Press has now released a new book We Can Do Better: Collected Writings on Land, Conservation, and Public Policy by Paul W. Johnson and edited by Curt Meine. Curt Meine is a conservation biologist, environmental historian, and writer based in Sauk County, Wisconsin. Meine has authored and edited several books, including the award-winning biography Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work and The Driftless Reader.