Steps Back in Time: Foot-Notes + Highlandville Dances

Foot-Notes Scandinavian Music Keeps Dancers Turning at Highlandville Schoolhouse

BY KRISTINE JEPSEN

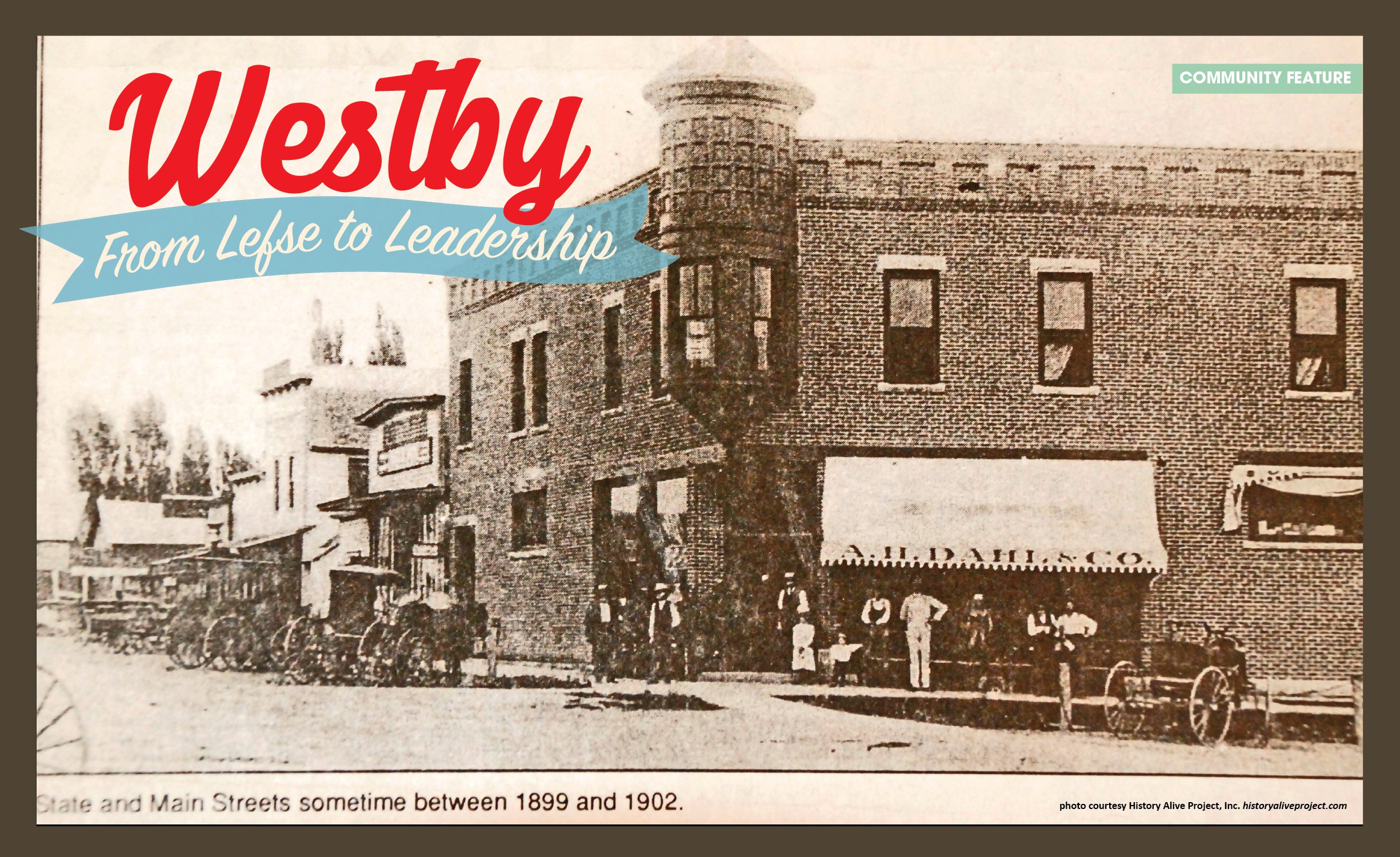

As the summer sun dips behind the bluffs in Northeast Iowa, cars nudge along the shaley white gravel to Highlandville, a quiet hamlet on South Bear Creek, one of Iowa’s most pristine trout fisheries. Drivers who haven’t been here before take the turns cautiously – cell reception and GPS mapping having dropped off miles ago – drifting slowly by the historic hospital building-turned-B&B, past the landmark Highland General Store and Campground, ‘til you can see your destination – Highlandville Schoolhouse – just across the creek, its porch light shining like a beacon.

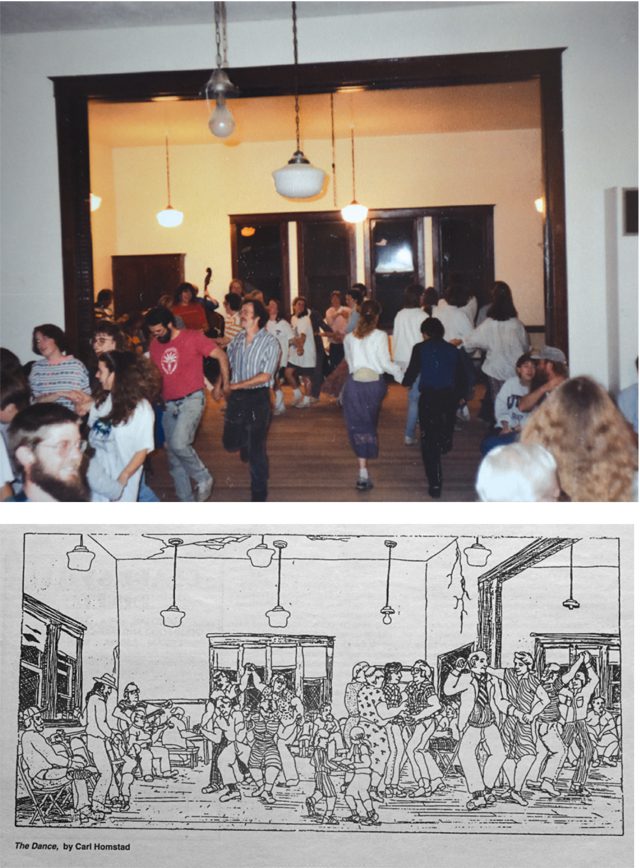

If your car windows are down as you drive in, you’ll hear the draw immediately: A fiddle, mandolin, guitar and upright bass – the acclaimed Decorah band Foot-Notes – are tuning up, and laughter and conversation spill through the open schoolhouse windows, where an eager crowd of all ages lines an open dance floor. Then, with a long draw across the fiddle strings, the first dance tune unfurls, in perfect time with the steps of partnered bodies. Another Highlandville dance is in motion.

It’s fun, yes, and welcoming – partners glad-hand away from each other as dance steps pick up. But deeper is the feeling that these celebrated events create a live connection between this Scandinavian community’s heritage and its future, as the music is passed down, measure-by-measure, artist-to-artist.

According to Foot-Notes founding fiddler, Beth Hoven Rotto, Highlandville School dances started around 1974 – before Foot-Notes time – when fiddlers Bill Sherburne and Johannes Sollien (and their bands) crossed paths with artists Dean and Geri Schwarz, who ran a pottery school in Highlandville, and Luis Torres, a local history professor at Luther College in Decorah. Acclaimed poet Joseph Langland, originally from the area, and his brother Walter (and Maurice) Langland of rural Highlandville also had a hand in rallying the community to share traditional waltzes, polkas, two-steps, and schottisches. The schottische, which can baffle the first-timer, is a partner dance akin to American square-dancing, but with few called figures and more trading places – sometimes partners – as the whole dance turns counterclockwise around the room. Left and right steps, turning steps, and hop steps are its trademarks.

It was about mid-century, says Foot-Notes bass player and Spring Grove, Minnesota, native Bill Musser, that the, uh, reserved Norwegian Lutherans loosened up a bit about the ‘impropriety’ of partner dancing, and the Highlandville Dances became an intergenerational draw. Older dancers, including locals Arnold Munkel and Lester and Genevieve Bentley, taught younger ones, with a palpable urgency to ensure that new enthusiasts understand the freedom and festivity of folk dancing. Born into a very musical farm family, Bill attended the early events. “I remember dancing past midnight sometimes,” he explains. “Just couldn’t get enough of it!”

Foot-Notes rhythm guitar player Jon Rotto (married to Beth, above) agrees that the opportunity felt extraordinary from the very beginning. “When I first discovered the dances in Highlandville, it was a huge relief over the ‘sock hop’ stress of having to make up your own moves to the rock music of high school and college,” he says of his days drifting the back roads to the schoolhouse as a student at Luther College. “The simple set of moves for each type of dance is predetermined, yet your creativity can take you beyond the basic dance, once you’re familiar.”

Highlandville School itself, built in 1911 and in service until 1964, commands a kind of reverence, Jon continues. “It’s not unlike a church, with its high ceilings and pendant lights – a vestige of an earlier time, with its outhouses and lack of indoor plumbing. Soon a sense of adventure starts lifting you along.”

Writing from his current home in Lørenskog, Norway, Jim Skurdall, Foot-Notes’ original mandolin player, says he never got over the lucky happenstance that seemed to crop up around traditional folk music – and the people playing it – in this corner of the Driftless. As a stranger road-tripping through Decorah in 1990, he – and a mandolin rented from Kephart’s Music – were invited off the cuff by Jon’s sister-in-law, Liz Rog, to what would be the first ever Foot-Notes tune-tooling session.

“After a potluck dinner, we struck up some music and exchanged a few tunes, but we didn’t know yet it was the start of something,” says Jim. The music itself convinced him to cancel his trek to the East Coast and stay – for what would be decades. Like the other members, he went on to pen tunes for the group and became beloved for his singing of old tunes in their native Norwegian. “I always enjoyed watching folks coming into the schoolhouse for the first time, usually with big grins on their faces, looks of amazement. The atmosphere says: ‘You’re new at this? So are we! Jump in!”

But – none of it happens without the live dance band, the music a bright torch passed on by Bill Sherburne and other old-timers. The person carrying that flame is fiddler Beth Rotto. In the 1980s, Beth was a violinist at Luther College and folk dance enthusiast. She sought out Sherburne directly when she heard murmurings of his retirement and asked to apprentice with him as part of an Iowa Arts Council grant.

“My heart sank, though, when I arrived at Bill’s door, and he looked less than enthused to see me,” she explains. “But everything changed when I brought Jon in on guitar, and suddenly, we had a band. Bill started preparing for our visits, often presenting tunes he claimed he hadn’t thought of in years. I attempted to copy everything about how he played – not just the music, but his bowing and sometimes even the set of his jaw. After our apprenticeship ended, I continued to play beside him for the rest of his life.”

Beth is Norwegian-modest about the music transcription she performs – a process she has mastered to Foot-Notes benefit, developing a shorthand for taking down tunes she hears on recordings, from other musicians, and at festivals. She’ll jot down chord progressions, writing the letters above or below the last to indicate which way the melody is moving on the scale. Then, as the tune repeats itself, she’ll sketch in how the measures break and other phrasing tips to jog her memory when she goes to reproduce it on her fiddle. “Usually by the third pass through – dance tunes tend to cycle in threes – I’ve got it,” she explains.

This skill is the key – it’s how folk music gets etched into recorded history and rejuvenated as new players take it up. All the Foot-Notes members are attuned to it, listening for pieces they haven’t heard before. “In the early days, Beth would call and leave messages on my home voicemail with a melody to a new tune,” Jim Skurdall says. “I would work up harmony lines and leave a message back. Then when we all got together to play, we had a new tune well underway.”

To date, Foot-Notes has more than 120 pieces on “active” recall, including polkas, waltzes, two-steps, schottisches, authentically Norwegian melodies, such as, “Orevalsen” and “Klemmet Ole,” and a group of songs they lovingly refer to as “miscellaneous.” Among them is the “Butterfly,” a tune that picks up in pace and intensity until dancers are fairly flying around the room. At one 1994 performance in the newly restored barn at Luther College, a dancer came down so hard he put his leg through the floor (unhurt, though!). “We refer to that dance as the time Foot-Notes brought down whole barns,” Jon jokes, though most performances – for private parties, weddings, anniversaries and other celebrations – don’t usually get so rowdy.

In 2015, commemorating 25 years together, Foot-Notes hosted the World’s Largest Schottische, with 1,881 registered dancers during Decorah’s annual Nordic Fest. See the video and purchase the World’s Largest Schottische dance tune at www.footnotes.dance/. The band has produced four full-length records so far, one of which, My Father Was a Fiddler, includes a companion tunebook. Foot-Notes also contributed to the 1996 Festival of American Folklife CD, Iowa State Fare: Music from the Heartland, a project of Smithsonian Folkways.

But the best introduction, if you’re so lucky, is to hear Foot-Notes in their native habitat – at a Highlandville Dance. As the night winds down and dancers begin to gather their discarded shoes and sweaters, or perhaps, to collect sleepy small children from the nests they’ve made in coats in the corner, you’ll hear one signature tune without fail: Highlandville Waltz. Penned by then-college-students, Greg Huang-Dale and Erik Sessions, this lilting dance signals the close of a sweet summer respite. It’s not the end, per se, but a gentle send-off, as for old friends. “Until next time,” it suggests, when no further words come.

“I can’t express it very well, but the value of community dancing is undeniable,” says current mandolin player John Goodin, who is beloved by his fellow band members for his ability to sub in and improvise on virtually every instrument between them. “Every single time, I come home a happier, healthier, and better person, thankful that I could be a small part of that special experience,” he says. “It is always a Good Thing.”

Kristine Jepsen is born-bred a Band Geek and considers the Highlandville dances, local contra dances, and other active musical treasures to be the most valuable assets of the Driftless community. When not barefoot on a wooden dance floor, she’s writing for literary journals and small businesses, with a deepening interest in life stories, end-of-life poetry, and other creative work as part of palliative care. More at kristinejepsen.com.

To keep time with Foot-Notes performances, join the public group on FaceBook: www.facebook.com/groups/footnotesfans/

Or find them online: www.footnotes.dance

The New Ole Hendricks Orchestra

Fiddler Beth Hoven Rotto is also in another band, The New Ole Hendricks Orchestra. Watch for their CD release concert in Decorah later this summer.

The recording features tunes rediscovered in a most amazing tale stretching across continents and generations painstakingly researched and reimagined by a surprising assemblage of far-flung performers.

Master fiddler Ole Hendricks (born 1851 in Norway – died 1935 in Minnesota) left a dancehall full of rare tunes in his 97-page, handwritten tunebook, which has miraculously survived and is now revived by Norwegian fiddler Vidar Skrede, local musician Beth Hoven Rotto, and seasoned performers Amy Shaw, Chris Bashor, David Tousley, and special guest, Bob Douglas.

CDs for both The New Ole Hendricks Orchestra and Foot-Notes are available at Vesterheim Museum Store and Oneota Community Co-op in Decorah or by contacting bethrotto@gmail.com.