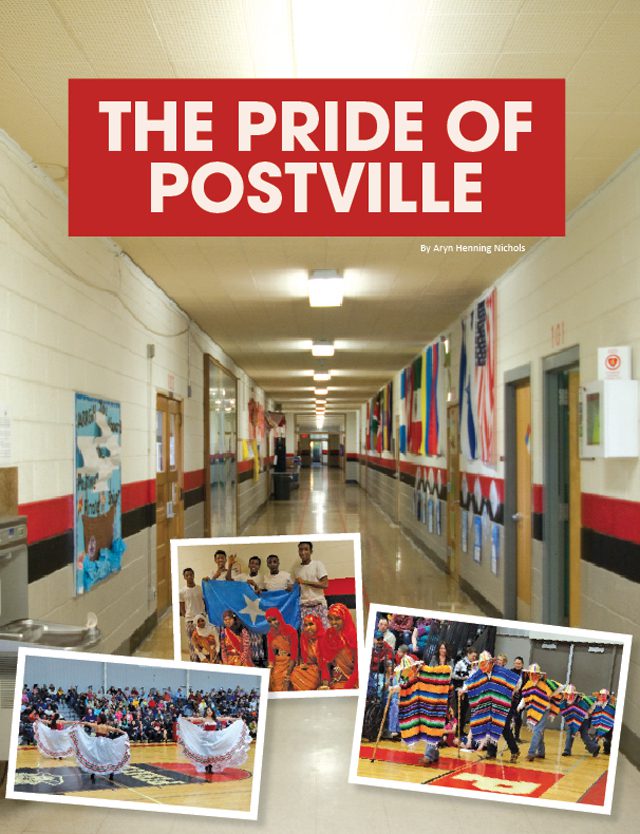

Community Feature: The Pride of Postville

The Pride of Postville

By Aryn Henning Nichols

Kids are kids.

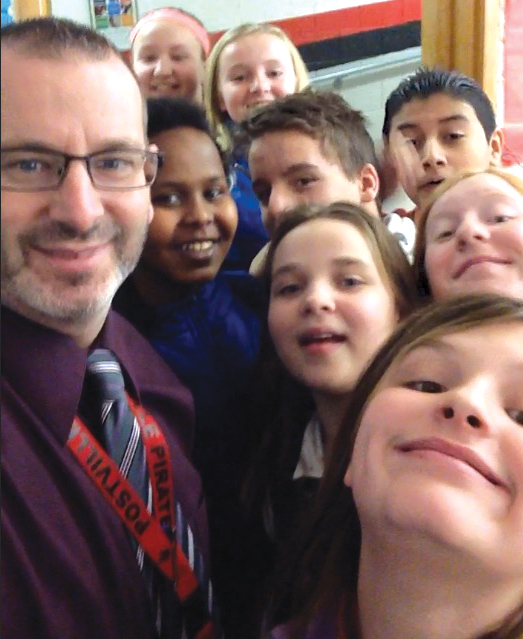

“They’re just kids. It doesn’t matter where they come from, if they speak the language or not, you still see them out in the hallway, you know, screwing around, being normal goofy kids,” says Postville Middle and High School Principal Brendan Knudtson.

But, unlike most other schools in the rural Midwest, skin colors span the spectrum at Postville Schools. Some students are dressed in traditional Muslim hijabs, others speak Spanish across the school parking lot, and still others maintain the blond-haired and blue-eyed look. Diversity isn’t a word traditionally associated with small towns in Northeast Iowa, but in the Postville community and Schools, it’s the word of the day, every day. And it’s their pride and joy.

“Postville is a solid rural community,” writes Mayor Leigh Rekow when asked about the town’s biggest attributes. “We accept change and adapt throughout our history. We have ordinary citizens who make outstanding efforts to grow and promote Postville. We have three large industries, one that has been here over 100 years, and our school remains independent and grows due to readily accepting diversity.”

Postville, a town of roughly 2,300 people, has been written about a lot, mainly because of one of those large industries – Agriprocessors (now Agri Star), a Kosher meat packing plant. Founded in 1987, Agriprocessors, over time, brought about 100 ultra orthodox Jewish families to the community. It also brought many immigrants seeking a decent life in the States, and, ultimately, it brought the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for the “largest raid of a workplace in U.S. history up to that date” – May 12, 2008. Nearly 400 immigrant workers were arrested for false identity papers, and more than 300 workers were convicted on document fraud charges. The majority served a five-month prison sentence before being deported.

Current 5th/6th grade technology teacher Lindsay Salinas wasn’t in Postville during the raid – she was teaching ESL kids, but in Arizona. Salinas followed the news closely, though, because Postville is her hometown, where she graduated from high school in 2001, and eventually where she would return to teach in 2009.

“When I first got back to Postville, I noticed how some kids would get jumpy or nervous out on the playground whenever a helicopter happened to fly over,” she says. “When word gets out that ICE is around the area there are some families that take off to visit relatives for awhile (which means the kids are pulled out of school). It really has a big impact on how things go at school for the kids that are still here too. The kids know when parents are nervous or scared about something and it’s obvious to us here at school when there is something like that going on because they start acting differently.”

Salinas and her husband, Hector – also a Postville graduate, and now a local police officer – live on a portion of the family farm where Salinas was raised. Their two kids romp around in the same fields where she herself played as a kid. But the diversity kids are exposed to throughout childhood in Postville has clearly evolved greatly.

“We didn’t really have many immigrant students in our classes until I was in Middle School in the mid-to-late 90s,” Salinas says. “It was a really cool thing for us (a bunch of small town kids) to have someone come from so far away, sometimes from very big cities, to our little town.”

These days, if there aren’t a good number of immigrants in a classroom, it’s unusual. At any given time, there are roughly 25-30 different countries represented throughout the school. In the past five years, Postville Schools have gone from 21 to 52 percent minority.

“We’re a majority minority school,” says Elementary School Principal Chad Wahls with a smile. “If there’s a week that goes by that we don’t get a new student, we’re surprised.”

Because of the transient nature of factory work, which makes up a large percentage of the jobs in Postville, many students come and go.

“It’s hard to get used to when students leave, because a lot of the time it’s very quickly,” Salinas says. “If we know more than a couple of days ahead of time, it’s nice because we get to say goodbye, but a lot of times we don’t get that much warning. And sometimes it’s as much warning as the kids have, too.”

But that doesn’t make the students’ impact on their teachers and administrators any less. The two principals have obvious pride over their students. They point out a large poster of elementary students’ school pictures smiling out, and they, well… gush.

“Look at this girl – she’s so darn great; the teachers fight over who gets to have her in class,” Wahls says, pointing to an adorable student with a crooked smile and colorful hijab.

Just like kids are kids, administrators are administrators (the good ones, anyway), and teachers are teachers. They love their work – why else would they take on such a tough career?

“Our kids are phenomenal,” Knudtson says. “I mean, you learn as much from them – their hardships, the stories, and the challenges. And it’s very important to take that into consideration – where these kids came from and where they want to go.”

“We’ve got the group of Somalis… and technically they’re refugees, we’ve got the legal immigrants, and we’ve got the illegal immigrants. And we can’t ask that. We just say, ‘Hey, come to school.’”

“We built infrastructure because we’ve had to,” Knudtson says. “You know, my first day here, I met Ali Aden, Ali was the first Somalian in the high school. No English. And I’m like, okay, what do you guys do when you get students with no English? And they said, ‘Just throw them in the classroom.’ And I was like – you guys have had this for years – how do we not have a pathway for those kids? After a few weeks, I realized we had about 10 of those non-English-speaking kids. That was the first year we basically blew up our schedule and created these newcomer-type course lines.”

Newcomer courses make the transition into the school system easier for both the non-English speaking students and the teachers and administrators as well. The students do two newcomer courses right away: life language (bathroom, lunch cards, lockers, etc), and one of four levels of ESL courses – A-D based on their level.

“We’ve had 16-17 year olds who haven’t been in school since 5th or 6th grade,” Knutson says.

“So we created foundation courses – science, math, social studies, and English – to try to get those back-skills so they can get on track. They might not get all through English 12 courses, but they can get close.”

Before the newcomer classes were in place, they’d lose students after a few weeks because they’d be sitting in class not understanding a word. Knudtson hired extra ESL teachers and a newcomer teacher to make things go smoother for everyone involved. And the system seems to be working.

“Seven of those 10 newcomers graduated last year. We took them from not a lick of English to a high school graduate.”

“With most of them reaching, on average, junior level classes. In four years, and that was through the work of the teachers,” Knudtson says. “It’s tough. The teachers are exhausted on Friday afternoon. But they’ll never stop caring. They’ll never stop coming to me and Mr. Wahls and saying, ‘Can we do this for these kids?’ and I’m like, ‘I don’t know if we can or I can, but you know, we’ve got to figure out how to get this in our system.’ And that’s part of the pride in our school and the pride in our kids.”

“Now we get calls from other districts saying, ‘We’ve got a student who doesn’t speak English. What do you do with them?’” Knudtson says.

In addition to having more help from teachers and administration, often other students who speak the needed language will step up to assist or translate. And even if they don’t speak the language, Postville kids have adopted a welcoming attitude toward the constant flow of new students.

“It’s so great to see how our kids interact with each other,” Salinas says. “There are times when I am just in awe of the fact that our Postville kids could be teaching lessons in tolerance and acceptance to a lot of adults I know. They don’t care what color you are or where you are from, or even if you speak the same language…if someone wants to play 4-Square together at recess or help someone to complete an assignment, that is all that matters. Kids are kids, they all enjoy the same things, but what’s great about our Postville kids is that they all have such different experiences and backgrounds – we all learn so much from each other.”

Luul Abdullahi, for instance, moved to Postville on American Independence Day. July 4, 2013, she and her family came from a huge city in the desert to the humidity of a Midwest summer. She (pictured above in a purple jacket and colorful hijab) was a Somalian refugee based out of Saudi Arabia, where students were separated by gender – boys with boys, girls with girls.

“That was the first huge cultural difference,” she says with a laugh. “We were used to talking about boys, not having them there right in front of us!”

She’s gotten used to it, she says, and doesn’t seem to have much time to talk about boys anyway. Principal Knudtson was instructed to tell Luul to cut back on her college credit courses, lest she be considered a full-time college student. She’ll head to Northeast Iowa Community College in the fall to study nursing. She’s happy to have moved to Postville, gotten to experience snow (a big deal for many of the students coming from desert or tropical climates), and to be a part of the diversity of the community.

“It feels like home,” she says with a shy smile.

“Everybody is their own person,” she continues. “They say America is like this melting pot, but I like to say it’s a salad bowl. We’re all unique, but we learn about each other’s customs and work together. There are certain things we agree upon and certain ones we don’t, but when you think about it, we’re not that different.”

Postville senior Melvin Munoz made his way with his family to Northeast Iowa 10 years ago, when he was just eight years old and in second grade. They had moved around a lot in El Salvador – from rural country living to the slums of city life – and, ultimately, to Postville for work.

Postville senior Melvin Munoz made his way with his family to Northeast Iowa 10 years ago, when he was just eight years old and in second grade. They had moved around a lot in El Salvador – from rural country living to the slums of city life – and, ultimately, to Postville for work.

“I’m grateful I experienced pretty much all types of cities in El Salvador,” Melvin says with a wise nod. “I came from a big city, so coming here to this little town – it was a big change. When I first came to Postville, my dad and a teacher were showing me around the school, and I was a little shy, but I got to my class and there were two Hispanic kids who said right away, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll play soccer with you at recess.’ It was a great introduction for me to Postville.”

The charismatic student is quick to list off the teachers and mentors who have inspired him – the fact that he already has a list makes Melvin seem pretty unique, but really, he’s like any other kid. He works a part time job at a local gas station and hangs out with friends, watching movies and NFL football games on the weekends. He plans to go to college in the fall – DMACC (Des Moines Area Community College) – and hopes to some day have a job that doesn’t tie him down to one place too much.

Melvin makes sure to look out for the younger kids in his family – he’s the oldest of four – as well as the kids coming in to school at Postville.

“Down to the center, we really do care about one another,” he says.

“It’s kind of great to see this diversity because when I came here to Postville, I was instantly comfortable. That’s what I’d like to see with the younger kids, you know.”

“I don’t believe I don’t have friends here. People I’ve never met, they’re like, ‘How you doing, Melvin?’ They know me, and that’s amazing to me!” he says. “The reason the town knows me is because I am involved. I’d say Postville’s downfall is that I don’t see the community encouraging the students who aren’t as involved.”

Melvin seems to have hit upon a theme that arose amongst folks in Postville: If they were to pick a downfall of the community, it would probably be a bit of a lack in volunteerism and general community involvement – from finding local volunteer firefighters to students to try out for wrestling or sign up for speech.

Ludvin Sarazua (pictured left), a 2014 graduate of Postville and current Postville Schools paraprofessional, would like to start a mentoring programencourage kids to be more involved in extracurricular activities. Sarazua’s job entails working one-on-one with certain students to help them learn a little faster. He’s a go-getter and hopes to be able to continue college one day soon. He went to Upper Iowa University for one year, but costs were prohibitive, so he was forced to take a break – a fairly regular occurrence for students coming out of Postville Schools. Many simply can’t afford to go, and, of course, for those students who may be undocumented, they don’t qualify for any additional funding at all.

Ludvin Sarazua (pictured left), a 2014 graduate of Postville and current Postville Schools paraprofessional, would like to start a mentoring programencourage kids to be more involved in extracurricular activities. Sarazua’s job entails working one-on-one with certain students to help them learn a little faster. He’s a go-getter and hopes to be able to continue college one day soon. He went to Upper Iowa University for one year, but costs were prohibitive, so he was forced to take a break – a fairly regular occurrence for students coming out of Postville Schools. Many simply can’t afford to go, and, of course, for those students who may be undocumented, they don’t qualify for any additional funding at all.

It was 2005, when Sarazua was in third grade, that he moved to Postville from Guatemala. He learned how to read by the end of that year, and clearly recalls his first day.

“Everyone was so accepting,” he says. “I always thought racism was a big thing that just existed, but really, it’s taught.”

This is a concept that many grown-ups can find uncomfortable to admit.

“When I’m with people (adults) from around Northeast Iowa who find out I am a teacher at Postville, inevitably the first question I get is something like, ‘Oh, and how is teaching in Postville with all that diversity?’ From the look I sometimes get, I feel like they are expecting me to say how hard it is and how much I wish I would be teaching in another nearby town instead… like they feel sorry for me maybe…,” Salinas says. “But my answer is that it’s great, it is a challenge every day, it is so rewarding – even when it’s hard – and I appreciate how much I learn from my kids everyday. I don’t want it to seem like I don’t want people to ask questions and talk about what Postville is like; I do for sure. But I don’t want people to enter into the conversation already thinking of us in a negative way. We’re a pretty amazing place.”

Postville pride has always been one of those phrases uttered throughout the history of Postville Schools – it’s one of the mottos, and it couldn’t be more deserving. The acceptance and love of their diversity truly is amazing.

“I’ve spent time teaching in other countries, in other states, and in other cities and Postville is so similar to everywhere else I have been…just a small town version instead of a big city,” Salinas continues. “I feel like students from Postville can leave here being prepared to go anywhere they can dream of going.”

—————————————-

Aryn Henning Nichols graduated from Postville High School in 1999. She wishes there had been as much diversity then as there is now (also that awesome fine arts building). She’s so proud of what the Postville students and faculty are up to these days.

Aryn Henning Nichols graduated from Postville High School in 1999. She wishes there had been as much diversity then as there is now (also that awesome fine arts building). She’s so proud of what the Postville students and faculty are up to these days.

—————————————-

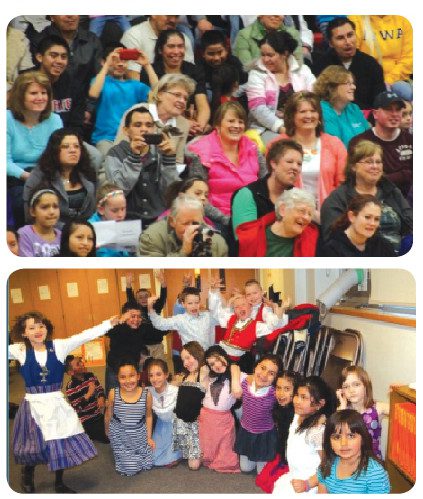

DIVERSITY CELEBRATION!

In 2013, the Postville Schools ESL team spearheaded a celebration of the diversity amongst the students, highlighting the motto “Together We Are Better”. A bi-annual festivity, students and their families come together in the high school gymnasium and public areas to teach attendees about their county’s customs through dances, demonstrations, foods, and fun. More than 1,000 people came to 2014’s celebration. The 2016 Diversity Celebration was held March 18, 2016. Check www.postville.k12.ia.us for future details. (All Diversity Celebration photos courtesy Postville Schools)

In 2013, the Postville Schools ESL team spearheaded a celebration of the diversity amongst the students, highlighting the motto “Together We Are Better”. A bi-annual festivity, students and their families come together in the high school gymnasium and public areas to teach attendees about their county’s customs through dances, demonstrations, foods, and fun. More than 1,000 people came to 2014’s celebration. The 2016 Diversity Celebration was held March 18, 2016. Check www.postville.k12.ia.us for future details. (All Diversity Celebration photos courtesy Postville Schools)